2. Zmienne, wyrażenia i instrukcję¶

2.1. Wartości i typy danych¶

Wartość jest jedną z podstawowych rzeczy — tak jak litera czy liczba – które przetwarza program. Wartości, które dotąd widzieliśmy to 4 (wynik naszego dodawania 2 + 2) oraz "Hello, World!".

Wartości podzielone są na różne klasy lub typy danych: 4 jest liczbą całkowitą (ang. integer), a "Hello, World!" jest napisem (ang. string - nazwany tak gdyż jest to “sznurek” liter). Możesz (tak jak interpreter) rozpoznać napisy ponieważ są one ujęte w cudzysłów.

Jeśli nie jesteś pewien do jakiej klasy należy dana wartość, Python posiada funkcję type (z ang. typ, rodzaj), która odpowie Ci na to pytanie.

>>> type("Hello, World!") <class 'str'> >>> type(17) <class 'int'>

Jak można się było spodziewać, napisy należą do klasy str (od “string”), a liczby całkowite do klasy int (od “integer”). Mniej oczywiste jest, iż liczby z dziesiętną częścią ułamkową należą do klasy float, ponieważ są one reprezentowane jako liczby zmiennoprzecinkowe (ang. floating-point). Na tym etapie, możesz traktować słowa klasa i typ jako synonimy. Dokładniejszym poznaniem znaczenia klasy zajmiemy się w dalszych rozdziałach.

>>> type(3.2) <class 'float'>

Co z wartościami takimi jak "17" czy "3.2"? Wyglądają jak liczby, ale są w cudzysłowach tak jak napisy.

>>> type("17") <class 'str'> >>> type("3.2") <class 'str'>

Są to napisy!

Napisy w języku Python zawarte są w apostrofach ('), cudzysłowach (") lub serii trzech trzech z tych znaków ('''` albo """)

>>> type('This is a string.') <class 'str'> >>> type("And so is this.") <class 'str'> >>> type("""and this.""") <class 'str'> >>> type('''and even this...''') <class 'str'>

Napisy w cudzysłowach mogą zawierać apostrofy, np. "alfabet Morse'a", a napisy w apostrofach mogą zawierać cudzysłów, np. 'Rycerze którzy mówią "Ni!"'.

Napisy zawarte w potrojonych cudzysłowach (lub apostrofach) mogą zawierać zarówno cudzysłowia jak i apostrofy:

>>> print('''"Oh no", she exclaimed, "Ben's bike is broken!"''') "Oh no", she exclaimed, "Ben's bike is broken!" >>>

Napisy z potrójnymi cudzysłowami mogą obejmować wiele linii:

>>> message = """This message will ... span several ... lines.""" >>> print(message) This message will span several lines. >>>

Python nie rozróżnia czy użyte zostały przez Ciebie apostrofy, cudzysłowy czy potrójne cudzysłowy do oznaczenia napisy: po wczytaniu treści programu lub komendy, są one przechowywane w identyczny sposób, a użyte znaki nie są częścią wartości. Jednak, gdy interpreter chce pokazać Ci napis, musi zdecydować jakiego rodzaju cudzysłowów użyć aby wyglądał on jak napis.

>>> 'This is a string.' 'This is a string.' >>> """And so is this.""" 'And so is this.'

W związku z tym autorzy języka Python zazwyczaj używają apostrofów do oznaczanie napisów. Jak myślisz, co się stanie jeśli napis już zawierał apostrofy?

When you type a large integer, you might be tempted to use commas between groups of three digits, as in 42,000. This is not a legal integer in Python, but it does mean something else, which is legal:

>>> 42000 42000 >>> 42,000 (42, 0)

Well, that’s not what we expected at all! Because of the comma, Python chose to treat this as a pair of values. We’ll come back to learn about pairs later. But, for the moment, remember not to put commas or spaces in your integers, no matter how big they are. Also revisit what we said in the previous chapter: formal languages are strict, the notation is concise, and even the smallest change might mean something quite different from what you intended.

2.2. Zmienne¶

Jedną z najistotniejszych funkcjonalności języka programowania jest jego zdolność do operowania na zmiennych. Zmienne są nazwami, które wskazują na wartość.

Instrukcja przypisania tworzy nowe zmienne i nadaje im wartości:

>>> message = "What's up, Doc?" >>> n = 17 >>> pi = 3.14159

Ten przykład wykonuje trzy przypisania. Pierwsze przypisuję wartość będącą napisem "What's up, Doc?" na nową zmienną nazwaną message. Następne kojarzy ze zmienną n liczbę całkowitą 17, a ostatnie przypisuję liczbę zmiennoprzecinkową 3.14159 zmiennej pi.

Nie należy mylić symbolu przypisania, =, z równością, która używa innego symbolu ==. Instrukcja przypisanie wiąże nazwę po lewej stronie operatora, z wartością po prawej stronie. Dlatego też otrzymasz błąd jeśli wpiszesz:

>>> 17 = n File "<interactive input>", line 1 SyntaxError: can't assign to literalWskazówka

Gdy czytasz lub piszesz kod, mów do siebie: “do n przypisuję 17-tkę”, albo “n otrzymuje wartość 17”. Nie mów “n równa się 17”.

Często spotykanym sposobem reprezentowania zmiennych na kartce papieru jest zapisywanie ich jako nazw oraz strzałek wskazujących na ich wartości. Taki zapis nazywamy obrazem stanu ponieważ przedstawia on stan każdej zmiennej w konkretnym momencie czasu. Następujący diagram przedstawia wynik wykonania powyższych instrukcji przypisania:

Jeśli poprosisz interpreter aby obliczył wartość zmiennej, poda on wartość która jest aktualnie powiązana z tą zmienną:

>>> message 'What's up, Doc?' >>> n 17 >>> pi 3.14159

W każdym z przypadku wynikiem jest wartość zmiennej. Zmienne mają też typy; tak jak wcześniej, możemy się zapytać interpreter jakie one są.

>>> type(message) <class 'str'> >>> type(n) <class 'int'> >>> type(pi) <class 'float'>

Typem zmiennej jest zawsze typ wartości do jakiej się ona odnosi.

Używamy zmiennych w programie aby “zapamiętywać” rzeczy, takie jak np. aktualny wynik meczu piłkarskiego. Oznacza to, że mogą się one zmieniać w czasie, tak samo jak może się zmieniać wynik meczu. Możesz zmiennej nadać pewną wartość, a później nadać inną wartość tej samej zmiennej. (Inaczej niż w matematyce, gdzie jeśli zmiennej `x` nadamy wartość 3, to nie może się ona zmienić na inną w połowie obliczeń!)

>>> day = "Thursday" >>> day 'Thursday' >>> day = "Friday" >>> day 'Friday' >>> day = 21 >>> day 21

Zauważ, że zmieniliśmy wartość zmiennej day trzy razy, a przy trzecim przypisaniu nawet nadaliśmy jej wartość zupełnie innego typu niż poprzednio.

A great deal of programming is about having the computer remember things, e.g. The number of missed calls on your phone, and then arranging to update or change the variable when you miss another call.

2.3. Nazwy zmiennych i słowa kluczowe¶

Variable names can be arbitrarily long. They can contain both letters and digits, but they have to begin with a letter or an underscore. Although it is legal to use uppercase letters, by convention we don’t. If you do, remember that case matters. Bruce and bruce are different variables.

The underscore character ( _) can appear in a name. It is often used in names with multiple words, such as my_name or price_of_tea_in_china.

There are some situations in which names beginning with an underscore have special meaning, so a safe rule for beginners is to start all names with a letter.

If you give a variable an illegal name, you get a syntax error:

>>> 76trombones = "big parade" SyntaxError: invalid syntax >>> more$ = 1000000 SyntaxError: invalid syntax >>> class = "Computer Science 101" SyntaxError: invalid syntax

76trombones is illegal because it does not begin with a letter. more$ is illegal because it contains an illegal character, the dollar sign. But what’s wrong with class?

It turns out that class is one of the Python keywords. Keywords define the language’s syntax rules and structure, and they cannot be used as variable names.

Python has thirty-something keywords (and every now and again improvements to Python introduce or eliminate one or two):

| and | as | assert | break | class | continue |

| def | del | elif | else | except | exec |

| finally | for | from | global | if | import |

| in | is | lambda | nonlocal | not | or |

| pass | raise | return | try | while | with |

| yield | True | False | None |

You might want to keep this list handy. If the interpreter complains about one of your variable names and you don’t know why, see if it is on this list.

Programmers generally choose names for their variables that are meaningful to the human readers of the program — they help the programmer document, or remember, what the variable is used for.

Ostrożnie

Beginners sometimes confuse “meaningful to the human readers” with “meaningful to the computer”. So they’ll wrongly think that because they’ve called some variable average or pi, it will somehow magically calculate an average, or magically know that the variable pi should have a value like 3.14159. No! The computer doesn’t understand what you intend the variable to mean.

So you’ll find some instructors who deliberately don’t choose meaningful names when they teach beginners — not because we don’t think it is a good habit, but because we’re trying to reinforce the message that you — the programmer — must write the program code to calculate the average, and you must write an assignment statement to give the variable pi the value you want it to have.

2.4. Instrukcje¶

A statement is an instruction that the Python interpreter can execute. We have only seen the assignment statement so far. Some other kinds of statements that we’ll see shortly are while statements, for statements, if statements, and import statements. (There are other kinds too!)

When you type a statement on the command line, Python executes it. Statements don’t produce any result.

2.5. Obliczanie wyrażeń¶

An expression is a combination of values, variables, operators, and calls to functions. If you type an expression at the Python prompt, the interpreter evaluates it and displays the result:

>>> 1 + 1 2 >>> len("hello") 5

In this example len is a built-in Python function that returns the number of characters in a string. We’ve previously seen the print and the type functions, so this is our third example of a function!

The evaluation of an expression produces a value, which is why expressions can appear on the right hand side of assignment statements. A value all by itself is a simple expression, and so is a variable.

>>> 17 17 >>> y = 3.14 >>> x = len("hello") >>> x 5 >>> y 3.14

2.6. Operatory i argumenty¶

Operators are special tokens that represent computations like addition, multiplication and division. The values the operator uses are called operands.

The following are all legal Python expressions whose meaning is more or less clear:

20+32 hour-1 hour*60+minute minute/60 5**2 (5+9)*(15-7)

The tokens +, -, and *, and the use of parenthesis for grouping, mean in Python what they mean in mathematics. The asterisk (*) is the token for multiplication, and ** is the token for exponentiation.

>>> 2 ** 3 8 >>> 3 ** 2 9

When a variable name appears in the place of an operand, it is replaced with its value before the operation is performed.

Addition, subtraction, multiplication, and exponentiation all do what you expect.

Example: so let us convert 645 minutes into hours:

>>> minutes = 645 >>> hours = minutes / 60 >>> hours 10.75

Oops! In Python 3, the division operator / always yields a floating point result. What we might have wanted to know was how many whole hours there are, and how many minutes remain. Python gives us two different flavours of the division operator. The second, called integer division uses the token //. It always truncates its result down to the next smallest integer (to the left on the number line).

>>> 7 / 4 1.75 >>> 7 // 4 1 >>> minutes = 645 >>> hours = minutes // 60 >>> hours 10

Take care that you choose the correct flavour of the division operator. If you’re working with expressions where you need floating point values, use the division operator that does the division accurately.

2.7. Type converter functions¶

Here we’ll look at three more Python functions, int, float and str, which will (attempt to) convert their arguments into types int, float and str respectively. We call these type converter functions.

The int function can take a floating point number or a string, and turn it into an int. For floating point numbers, it discards the decimal portion of the number — a process we call truncation towards zero on the number line. Let us see this in action:

>>> int(3.14) 3 >>> int(3.9999) # This doesn't round to the closest int! 3 >>> int(3.0) 3 >>> int(-3.999) # Note that the result is closer to zero -3 >>> int(minutes / 60) 10 >>> int("2345") # Parse a string to produce an int 2345 >>> int(17) # It even works if arg is already an int 17 >>> int("23 bottles")

This last case doesn’t look like a number — what do we expect?

Traceback (most recent call last): File "<interactive input>", line 1, in <module> ValueError: invalid literal for int() with base 10: '23 bottles'

The type converter float can turn an integer, a float, or a syntactically legal string into a float:

>>> float(17) 17.0 >>> float("123.45") 123.45

The type converter str turns its argument into a string:

>>> str(17) '17' >>> str(123.45) '123.45'

2.8. Order of operations¶

When more than one operator appears in an expression, the order of evaluation depends on the rules of precedence. Python follows the same precedence rules for its mathematical operators that mathematics does. The acronym PEMDAS is a useful way to remember the order of operations:

Parentheses have the highest precedence and can be used to force an expression to evaluate in the order you want. Since expressions in parentheses are evaluated first, 2 * (3-1) is 4, and (1+1)**(5-2) is 8. You can also use parentheses to make an expression easier to read, as in (minute * 100) / 60, even though it doesn’t change the result.

Exponentiation has the next highest precedence, so 2**1+1 is 3 and not 4, and 3*1**3 is 3 and not 27.

Multiplication and both Division operators have the same precedence, which is higher than Addition and Subtraction, which also have the same precedence. So 2*3-1 yields 5 rather than 4, and 5-2*2 is 1, not 6.

Operators with the same precedence are evaluated from left-to-right. In algebra we say they are left-associative. So in the expression 6-3+2, the subtraction happens first, yielding 3. We then add 2 to get the result 5. If the operations had been evaluated from right to left, the result would have been 6-(3+2), which is 1. (The acronym PEDMAS could mislead you to thinking that division has higher precedence than multiplication, and addition is done ahead of subtraction - don’t be misled. Subtraction and addition are at the same precedence, and the left-to-right rule applies.)

Due to some historical quirk, an exception to the left-to-right left-associative rule is the exponentiation operator **, so a useful hint is to always use parentheses to force exactly the order you want when exponentiation is involved:

>>> 2 ** 3 ** 2 # The right-most ** operator gets done first! 512 >>> (2 ** 3) ** 2 # Use parentheses to force the order you want! 64

The immediate mode command prompt of Python is great for exploring and experimenting with expressions like this.

2.9. Operations on strings¶

In general, you cannot perform mathematical operations on strings, even if the strings look like numbers. The following are illegal (assuming that message has type string):

>>> message - 1 # Error >>> "Hello" / 123 # Error >>> message * "Hello" # Error >>> "15" + 2 # Error

Interestingly, the + operator does work with strings, but for strings, the + operator represents concatenation, not addition. Concatenation means joining the two operands by linking them end-to-end. For example:

The output of this program is banana nut bread. The space before the word nut is part of the string, and is necessary to produce the space between the concatenated strings.

The * operator also works on strings; it performs repetition. For example, 'Fun'*3 is 'FunFunFun'. One of the operands has to be a string; the other has to be an integer.

On one hand, this interpretation of + and * makes sense by analogy with addition and multiplication. Just as 4*3 is equivalent to 4+4+4, we expect "Fun"*3 to be the same as "Fun"+"Fun"+"Fun", and it is. On the other hand, there is a significant way in which string concatenation and repetition are different from integer addition and multiplication. Can you think of a property that addition and multiplication have that string concatenation and repetition do not?

2.10. Input¶

There is a built-in function in Python for getting input from the user:

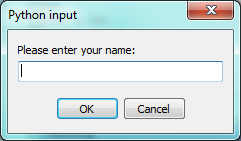

A sample run of this script in PyScripter would pop up a dialog window like this:

The user of the program can enter the name and click OK, and when this happens the text that has been entered is returned from the input function, and in this case assigned to the variable n.

Even if you asked the user to enter their age, you would get back a string like "17". It would be your job, as the programmer, to convert that string into a int or a float, using the int or float converter functions we saw earlier.

2.11. Composition¶

So far, we have looked at the elements of a program — variables, expressions, statements, and function calls — in isolation, without talking about how to combine them.

One of the most useful features of programming languages is their ability to take small building blocks and compose them into larger chunks.

For example, we know how to get the user to enter some input, we know how to convert the string we get into a float, we know how to write a complex expression, and we know how to print values. Let’s put these together in a small four-step program that asks the user to input a value for the radius of a circle, and then computes the area of the circle from the formula

Firstly, we’ll do the four steps one at a time:

Now let’s compose the first two lines into a single line of code, and compose the second two lines into another line of code.

If we really wanted to be tricky, we could write it all in one statement:

Such compact code may not be most understandable for humans, but it does illustrate how we can compose bigger chunks from our building blocks.

If you’re ever in doubt about whether to compose code or fragment it into smaller steps, try to make it as simple as you can for the human to follow. My choice would be the first case above, with four separate steps.

2.12. The modulus operator¶

The modulus operator works on integers (and integer expressions) and gives the remainder when the first number is divided by the second. In Python, the modulus operator is a percent sign (%). The syntax is the same as for other operators. It has the same precedence as the multiplication operator.

>>> q = 7 // 3 # This is integer division operator >>> print(q) 2 >>> r = 7 % 3 >>> print(r) 1

So 7 divided by 3 is 2 with a remainder of 1.

The modulus operator turns out to be surprisingly useful. For example, you can check whether one number is divisible by another—if x % y is zero, then x is divisible by y.

Also, you can extract the right-most digit or digits from a number. For example, x % 10 yields the right-most digit of x (in base 10). Similarly x % 100 yields the last two digits.

It is also extremely useful for doing conversions, say from seconds, to hours, minutes and seconds. So let’s write a program to ask the user to enter some seconds, and we’ll convert them into hours, minutes, and remaining seconds.

2.13. Glossary¶

- assignment statement

A statement that assigns a value to a name (variable). To the left of the assignment operator, =, is a name. To the right of the assignment token is an expression which is evaluated by the Python interpreter and then assigned to the name. The difference between the left and right hand sides of the assignment statement is often confusing to new programmers. In the following assignment:

n = n + 1

n plays a very different role on each side of the =. On the right it is a value and makes up part of the expression which will be evaluated by the Python interpreter before assigning it to the name on the left.

- assignment token

- = is Python’s assignment token, which should not be confused with the mathematical comparison operator using the same symbol.

- composition

- The ability to combine simple expressions and statements into compound statements and expressions in order to represent complex computations concisely.

- concatenate

- To join two strings end-to-end.

- data type

- A set of values. The type of a value determines how it can be used in expressions. So far, the types you have seen are integers (int), floating-point numbers (float), and strings (str).

- evaluate

- To simplify an expression by performing the operations in order to yield a single value.

- expression

- A combination of variables, operators, and values that represents a single result value.

- float

- A Python data type which stores floating-point numbers. Floating-point numbers are stored internally in two parts: a base and an exponent. When printed in the standard format, they look like decimal numbers. Beware of rounding errors when you use floats, and remember that they are only approximate values.

- int

- A Python data type that holds positive and negative whole numbers.

- integer division

- An operation that divides one integer by another and yields an integer. Integer division yields only the whole number of times that the numerator is divisible by the denominator and discards any remainder.

- keyword

- A reserved word that is used by the compiler to parse program; you cannot use keywords like if, def, and while as variable names.

- modulus operator

- An operator, denoted with a percent sign ( %), that works on integers and yields the remainder when one number is divided by another.

- operand

- One of the values on which an operator operates.

- operator

- A special symbol that represents a simple computation like addition, multiplication, or string concatenation.

- rules of precedence

- The set of rules governing the order in which expressions involving multiple operators and operands are evaluated.

- state snapshot

- A graphical representation of a set of variables and the values to which they refer, taken at a particular instant during the program’s execution.

- statement

- An instruction that the Python interpreter can execute. So far we have only seen the assignment statement, but we will soon meet the import statement and the for statement.

- str

- A Python data type that holds a string of characters.

- value

- A number or string (or other things to be named later) that can be stored in a variable or computed in an expression.

- variable

- A name that refers to a value.

- variable name

- A name given to a variable. Variable names in Python consist of a sequence of letters (a..z, A..Z, and _) and digits (0..9) that begins with a letter. In best programming practice, variable names should be chosen so that they describe their use in the program, making the program self documenting.

2.14. Ćwiczenia¶

Take the sentence: All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy. Store each word in a separate variable, then print out the sentence on one line using print.

Add parenthesis to the expression 6 * 1 - 2 to change its value from 4 to -6.

Place a comment before a line of code that previously worked, and record what happens when you rerun the program.

Start the Python interpreter and enter bruce + 4 at the prompt. This will give you an error:

NameError: name 'bruce' is not defined

Assign a value to bruce so that bruce + 4 evaluates to 10.

The formula for computing the final amount if one is earning compound interest is given on Wikipedia as

Write a Python program that assigns the principal amount of R10000 to variable p, assign to n the value 12, and assign to r the interest rate of 8%. Then have the program prompt the user for the number of months t that the money will be compounded for. Calculate and print the final amount after t months.

Evaluate the following numerical expressions in your head, then use the Python interpreter to check your results:

- >>> 5 % 2

- >>> 9 % 5

- >>> 15 % 12

- >>> 12 % 15

- >>> 6 % 6

- >>> 0 % 7

- >>> 7 % 0

What happened with the last example? Why? If you were able to correctly anticipate the computer’s response in all but the last one, it is time to move on. If not, take time now to make up examples of your own. Explore the modulus operator until you are confident you understand how it works.

You look at the clock and it is exactly 2pm. You set an alarm to go off in 51 hours. At what time does the alarm go off? (Hint: you could count on your fingers, but this is not what we’re after. If you are tempted to count on your fingers, change the 51 to 5100.)

Write a Python program to solve the general version of the above problem. Ask the user for the time now (in hours), and ask for the number of hours to wait. Your program should output what the time will be on the clock when the alarm goes off.